-

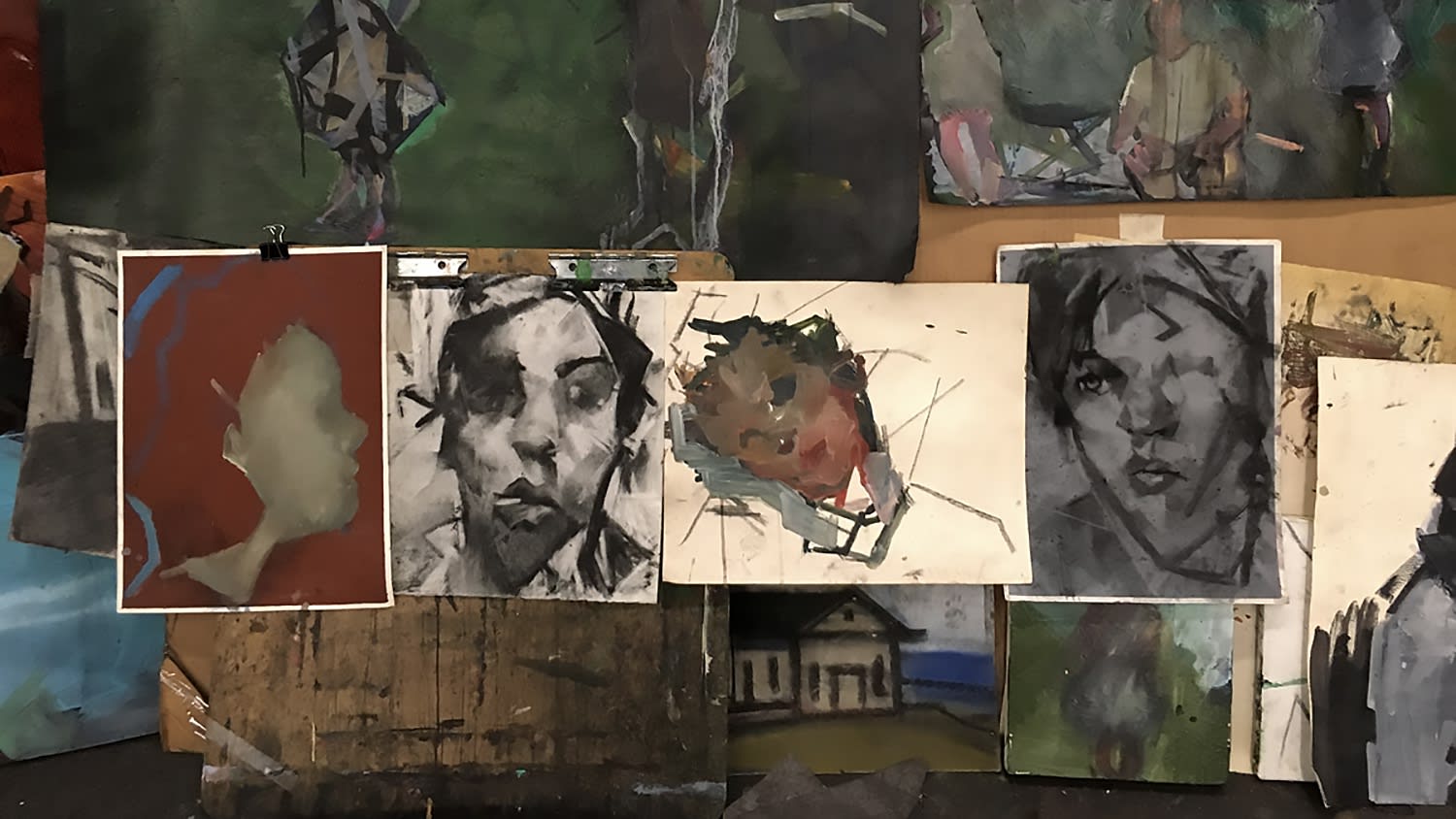

Image of Ruth Franklin, Golden Isles, One-Woman Show of paintings at Different Trains Gallery

Image of Ruth Franklin, Golden Isles, One-Woman Show of paintings at Different Trains Gallery -

-

-

-

-

-

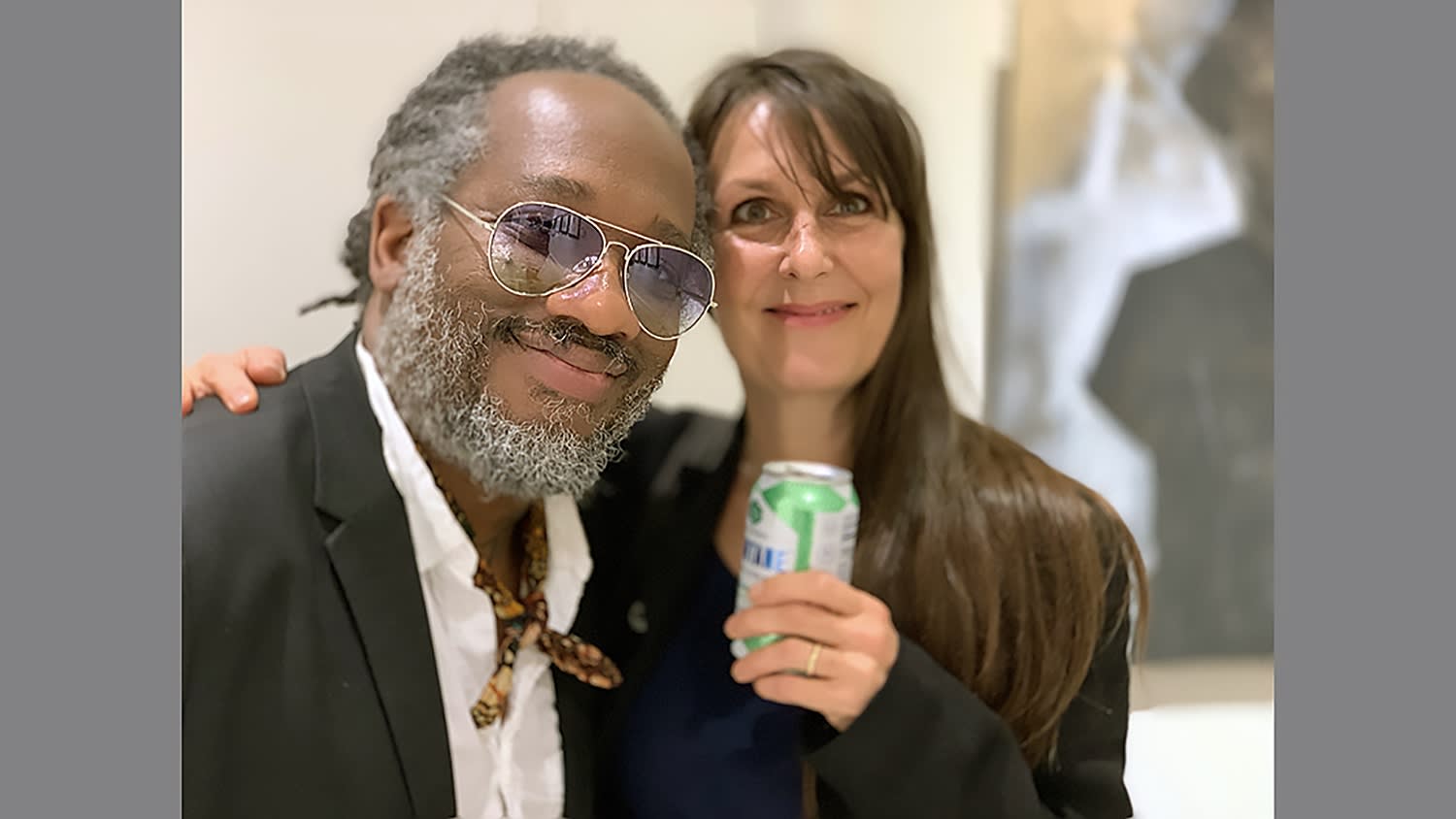

Image of artwork by Yehimi Cambron and Caomin Xie at the Waddi art gallery in Atlanta

Image of artwork by Yehimi Cambron and Caomin Xie at the Waddi art gallery in Atlanta -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Thank you for visiting VINSONart.com.

We're an Atlanta-based art consultancy and purveyor of Contemporary and Outsider Art by local and internationally recognized Artists, currently based at Different Trains Gallery in Decatur's Old Depot District. The gallery is open by appointment and for quarterly pop up shows.

The artworks on this website are curated and rotated regularly to provide an overview of our diverse roster of artists. Should you wish to see more available works by a particular artist, or schedule an appointment with Shawn Vinson, please give us a call or send an email.

Join our email list and follow us on Instagram to receive art updates and invitations to exhibitions and events.